Visualizing Change Through Interactive Photography: Transforming Identities, Transforming Research

While researching material for this blog on a broad range of topics, (but with the clear focus of how to present thinking about photography and imagery in new ways) I came across a wonderful piece in the: Hmong Studies Journal, Volume One Number One, Fall 1996 Titled: Visualizing Change Through Interactive Photography: Transforming Identities, Transforming Research written by cultural anthropologist Sharon Bays.

When Sharon wrote this piece she was an anthropologist “gathering hard data from adults” living in Visalia an agricultural town in California’s San Joaquin Valley. As she describes in her paper she was taking a fairly traditional approach to working with and studying this specific group of people. But, via some prompting of two Hmong children to show them how “to make pictures” she realized by teaching them the physical mechanisms of how “to make pictures” with a camera and allowing them to use her camera to express themselves and explore their own identities this would give her further access and understanding into the culture she was studying while “gathering hard data from adults.”

Giving two children access to cameras to explore their own identities gave her an entirely new way to explore their cultural identities both through them and in an interactive way with them. She states:

“It was these very fresh, intimate and compelling images, both the color and the black and white, shot mainly when I was not right there, that convinced me that their photographs reflected their culture and community in a way that mine could not.”

Further stating:

“For Jamie and Pang our project came to be about their struggle as emerging artists that reflected their own unique young Hmong perspectives, which often clashed with those of their elders. Our ongoing dialogues became the grounds on which they tested their ideas about language, love and sex, and, for 15 year old Pang, the courage to redefine “traditional” concepts of marriage. They both tried on aspects of their culture to check the fit, rejecting some parts while embracing others. And they both endured considerable criticism from some members of their community for hanging out so much at my place.”

You ask – Ok, interesting story, but so what? What’s your point?

Photography is often thought about in the following ways or layers:

1.) First, people think about photography in terms of it’s tools. Or the camera.

2.) Secondly, photography is thought about in terms of it’s products. The photos.

3.) But, there are other levels. Like thinking about photography in terms of the process of creating the images and even deeper in terms of relationships that develop in the process of creating images. Thinking about photography in this way could mean that neither the tools nor the products are as important as the process or the interaction. And I would argue that this is more often the case than not.

Using our example above Sharon later explains:

“It was also the work with the children that pointed to the inherent difficulties of turning such comfortable ethnographic traditions on their heads. Once relations had changed and barriers broke down, I entered into a deeply personal realm of interaction that no anthropological text even hinted at how I might proceed.”

Why is this important? Whether you’re a professional photographer, or an editor, or a creative at an ad agency, or any person concerned with the output of images for your job – you have to remember that things change in the process of creating images, relationships change, the meaning behind the images change, even the purpose and function of the images can change. Very often image creators and image consumers don’t recognize the importance of the creation process in terms of the meaning or value of a given image or set of images.

I encourage you all in the future to think deeper about the imagery you create and consume. Ask yourself not what camera was used to create a given image, or even for what purpose, but try asking yourself – what happened during the process of creating this image? You might start to see all imagery in an entirely new way.

48 Days of Efficiency: The Experiment – Part 2

The Process

Step Two: Refocusing & Planning

During my process of slowing down and re-centering I’ve also been thinking about how to move forward in all aspects of my life. Including how to move forward with my business, my health, all the way down to where I live and why. In doing so I have created a plan. An action plan.

However, for now the specifics of this plan aren’t as important as the process. And the process of carrying out my plan has to do with its structure and execution. Essentially I’m creating a set of rules for myself to create a space and time from with to work or carry out my plan within.

A Structure from with to Execute a Plan

Here is the structure for my plan of moving towards becoming more energy efficient in my life and my business:

1.) For the first time in well over 10 years I am going to get up at the exact same time every single day for 48 days in a row.

2.) For the first time in my entire life – I am going to go to bed at the exact same time every single night for the next 48 days in a row.

3.) I am going to eat breakfast and dinner at the exact same time for the next 48 days in a row.

The underling idea or goal behind doing these first 3 steps is to create a rigid frame to work within, or in other words – I have the exact same amount of time everyday to use my energy. No more staying up all night to work on something only to sleep half of the next day away. And no more not eating anything for breakfast because I had a bunch of morning meetings and didn’t get up early enough to eat. etc. etc.

I am not a morning person. And I never have been. Mornings are my Jedi kryptonite. However, for the purposes of this experiment in efficiency I am going to set a reasonably early (for me) time to wake up each morning.

Over the last few weeks I have read a number of different thoughts on how getting up early lends itself to being generally more productive. And I have generally stated throughout my life that I am way more productive at night. But, I am willing to see if there is some magical thing I have been missing all these years and to test this theory out for myself.

I recently read two blog posts by Leo Babauta titled: How I Became an Early Riser & My Morning Routine. Both of these posts made a lot of sense to me and are a part of my new ‘structure’ from which I will be executing my new plan towards efficiency in my life and business.

48 Days of Efficiency: The Experiement – Part 1

The Problem

Over the last few years I’ve become increasingly frustrated with a few major aspects of my life. They are as follows:

1.) I am unhappy with the amount of packaged foods I consume. I would like to no longer consume any food that comes in unnecessary packaging.

2.) I exercise in waves. I will exercise regularly for a few months and then not at all for a few months. Overall my commitment to my own physical health is inconsistent and I feel less physically healthy than I would like to be. I am not overweight or extremely out of shape. But, I am not in top physical condition and I would like to be.

3.) I have absolutely zero consistency in my daily life. I don’t have a single activity beyond walking my dog, eating, sleeping, and brushing my teeth (none of which I do at the same time each day on a daily basis) that I do daily.

4.) I do not use my energy with enough efficiency. Bottom line – I waste too much time.

The Process

A few months ago I started talking with a good friend of mine who owns a Minneapolis based photographic equipment rental company called Flashlight about how I was feeling like I wasn’t using my energy properly in many aspects of my life including my business. These conversations motivated me to explore this idea more deeply and try to identify the specific aspects of my life I feel like are least efficient and how I can move towards becoming the most productive person I can be.

Step One: Re-Centering

As an effort to move myself closer to my new goal of optimal energy efficiency I’ve made a few starter adjustments. They are the following:

1.) I’ve joined an indoor rock climbing gym and have gone at least 3 or more times a week for the last month. Besides climbing I have been running 5 or more miles twice a week as well.

2.) I’ve been sleeping more and don’t set an alarm clock. I sleep for as long as I feel like and set meetings for later in the day to allow for me to sleep in if I feel like it.

3.) I’ve been doing a lot more writing. Writing personal letters, blog posts, e-mails, and portions of a novel.

4.) I’ve been reading and thinking about the best way to move towards more efficiency.

5.) I documented and organized all of my 2010 financial information for my business for the year up to the current date.

6.) I’ve been turning down work. And have been doing less overall.

Someone reading these might at first glance think one or more of these actions might seem like adjustments in the opposite direction of optimal energy efficiency. My arguments against that thought would be this:

1.) Before taking these steps I was burnt out. I have been working harder than I realized over the last few years and had simply started to lose energy.

2.) I was starting to feel although I’ve been working hard. I haven’t been working smart enough or efficient enough and I haven’t been making as much money as I could be if I was more efficient with my time and energy. Therefore, doing less, sleeping more, writing more, and getting one important aspect of my life organized has helped center me.

Without even being completely aware of it I have actually been doing this for about the last 2 months. I have been slowly… slowing myself down. I have been doing this to get reorganized, re-centered, and re-balanced to move forward towards prime efficiency again. Because I have at various years in my life felt like I was living at a very high-level of efficiency, which is something that adds to my overall happiness. And unlike some people I actually really enjoy an effective and forward-moving day of hard work.

The 12 Best TED Photography Talks & Why

One of my goals is to someday be asked to give a TED talk. And not simply because I think it would be a great honor, but because I hope to someday have something so worthwhile to share that a TED conference would be an appropriate stage for my message. I am a huge fan of the TED conferences and it’s mission of ‘ideas worth spreading’. Of the 800 or so talks uploaded for public viewing I’m sure I’ve seen at least a few hundred of them over the last few years and they almost always are interesting and inspiring to me. I recently made a point to watch every single video that has any connection to photography or was given by a photographer and compiled my list of the most important video talks here.

A part of the purpose of The Photo Jedi blog is to be able to think out loud on topics I don’t feel are being covered elsewhere.

I picked each of these talks for different reasons, which I will explain further above each video, but the overarching reason why I connected with each of these videos was because they all require you to think.

Think.

As a working professional photographer one of the things I’m most frustrated with right now in the action of – taking, creating, or making a photograph – is that because it’s more easy than ever to take a photo professionals, prosumers, and amateurs alike are thinking less about what and why they are creating imagery.

Photography has become a universal action. And more and more a universally thoughtless action. For me, this is a bad, bad thing because photographic imagery can also be one of the greatest forces in human interaction on earth.

David Griffin: On How Photography Connects Us

(I selected this video to be the first one here because as the title suggests it serves as a great reminder as to how important photography really is. There is a famous, cliche even, line – “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Which, I have argued before is not the case… in fact, photographs can be even more powerful than a thousand words because they have the ability to present extremely complex things without having to use a single one. The power in photography is it’s ability to convey meaning beyond words. It’s simply amazing.)

Jonathan Klein: Photos That Changed The World

(Jonathan says: “When we are confronted with a powerful image we all have a choice – we can look away or we can address the image.” He goes further by saying: “Did the images change the world? No. But, they had a major impact.” Again, this is a message about the raw power of photographic imagery.)

James Balog: Time Lapse Proof of Extreme Ice Loss

(Using 25 time-lapse cameras positioned at the poles James has captured extremely clear and telling visual proof of global warming. This video scares the shit out of me. It reaffirms all of my fears for what our future on this planet might be like. If you can’t understand the power behind photography after watching this – you never will.)

Vik Muniz: Makes Art with Wire & Sugar

(I love this video because I don’t think Vik would define himself as a photographer, but he does create a lot of photography in his work. This video is important to me because it clearly states my underling thought for this post. You must think first – then shoot. And Vik is all thinking…. what a wonderful artist.)

Rob Forbes: On Ways of Seeing

(Like Vik’s video Rob also speaks to thinking about the world in a new way. But, his way of thinking involves a process of seeing things as they already are, but from a different point of view.)

Johnny Lee: Demos Wii Remote Hacks

(This is an important video because it combines the idea of thinking about photography in a new way with thinking about technology in a new way. He takes technology that exists for one purpose and re-purposes it for another use.)

Alison Jackson: Looks at Celebrity

(This video is also important for me because it really challenges what is considered a reasonable thing for a photographer to be allowed to do. Alison’s work challenges cultural conventions. This is important because it can serve to remind us that there are no rules when it comes to art or photography. Her talk reminds you that your work can be whatever you want it to be.)

Taryn Simon: Photographs Secret Sites

(I love Taryn’s project. I love it because it’s such a good idea. But, I also love her project because even though it was a really good idea for a photographic project her imagery is also really amazing. Which is ultimately what matters in the photographic arts. If you’re imagery can’t convey your message or stand on it’s own merits – then why is photography your medium? Why not use another form of expression to convey your idea?)

David Hoffman: On Losing Everything

(David’s says in his talk, “You gotta make something good out of something bad.” That’s an amazing message coming from a person who has lost the physical form of his entire life’s work in photography, film, and writing.)

Chris Jordan: Pictures Some Shocking Stats

(Another project I love. The ideas behind Chris’s work for me are some of the most important to be presented by a photographer now – period. Every person in the world should see his work.)

Yann Arthus-Bertrand: Captures Fragile Earth in Wide-Angle

(Yann says: “The problem is that we don’t want to believe what we know.” – indeed.)

Rachel Sussman: The World’s Oldest Living Things

(like Taryn and Chris’s projects I absolutely love the idea behind this project. And I’m actually a little jealous I didn’t think of it first… I love all things old. And nothing seems more important then to appreciate and respect the oldest living things on earth. Kind of helps you frame our place and time…. a little bit of an ego check, eh?)

Curator Interview 1: David Little — Head of the Department of Photographs for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts

(On January 6, 2010 I did an interview with David Little who is the Head of the Department of Photography and New Media for the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. This interview was originally intended for a publication that went out of business along with about 300 hundred other magazines in 2010. Since the original publication went under this interview sat dormant in the catacombs of my laptop all year. I really enjoyed speaking with David and definitely learned some new things about major museum curators. David curates a few special photo events each year called New Pictures featuring an individual photographer of his choice for a solo show at the MIA. My interview questions were all questions I was personally interested in and were not focused on a single topic or theme so we covered a lot of ground in our conversation.)

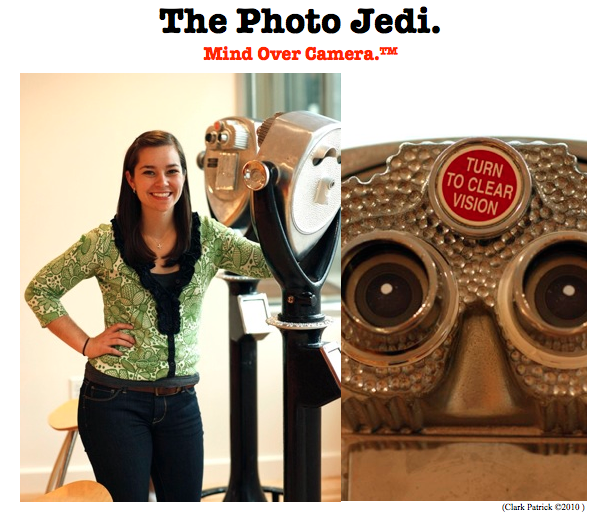

Would a museums or gallery ever display a photographic work on a digital screen? I think most people think of fine arts photography as something that stays in a printed form. Do you think this will ever change?

Yes, we could and maybe would display photographs in a digital format. But it would have to be a format that the given artist wanted to show it in. You wouldn’t take works from your collection and present them on digital screens if that is not how the original artists had intended for the work to be viewed. For instance, I guest curated a show for the Minneapolis Photography Society that the wall text said I based my selection on JPEGs. And that I was certain there would be a lot of surprises when I was able to see my final selections in print. The whole idea of looking at something as a JPEG and then as printed matter, or in a book, are very, very different things.

An interesting example we have here are some of our Ansel Adams pieces. If you go upstairs we have a comparison of an early Adams to a late Adams. The late Adams has much more contrast and has a new modern look. The early Adams has a very broad range of grays and much more detail in the texture. For a curator it’s the better print, but I think for a lot of people coming in, or those people who may have seen Ansel Adams’ work in a book, the second print is the right print. And then along side of it there’s that weird other print that has funny grays and it’s even bleached out a bit. Anyway, this is a long way of saying that we wouldn’t purposefully show a piece on a screen unless that was how the artist wanted it to be shown.

Does the MIA have a lot of its permanent photographic collection viewable online?

Yes. The MIA was really out of the game for a while before I started here. When you look at our digital collection, it looked like it was done maybe three years ago, but it was actually created closer to eight years ago. We have about 11,500 photographs in our collection. We had about 3300 online when I started, but now we’ve probably only got about another 500 photographs before we’ll have them all digitally scanned and viewable online. We’re now redoing our website and my goal is that within the next year we’ll have our entire photography collection online. We are here to be a resource and we want people to be able to see everything we have in our department.

I thought it was interesting that the title of your department is the, ‘Department of Photography and New Media.’ The ‘new media’ part is what I’m really interested in, because I think that’s a lot of what’s happening in the world right now. Do you curate for things that are mixed digital media or video pieces? What about things like CGI art or other things along those lines? How do you incorporate that into your collection?

This is a completely new thing for us and is a change that has happened within the last month. We purchased our first video piece, which was a large scale work. It hasn’t been seen yet. It is going to be seen in our exhibition in April. I have a show that is happening in the fall where I’ll have at least three or four video works. I think this type of work is a natural evolution of post 1960’s art, which is an area that I’m trying to develop. Our collection is fairly traditional and isn’t well developed past the late 1960’s. It falls off after that. My role is to really start collecting from the 60’s up to the present day.

What happens from the 60’s to the present is a kind of breakdown. Actually, it’s not a breakdown… A better way to describe it is that it become more of an opening up of other medias or, the whole idea of artists using photographs in new ways as opposed to ‘photographers’ creating images in the traditional sense. Artists have started playing around with a lot of the pre-scripted categories. In any case, an outgrowth of this category is that photographers now make videos. In a museum we have to decide where that type of work should exist. And we decided in makes most sense in our department. ‘Contemporary Art’ is another department that will also collect video. We will work very closely together on video purchases in new media.

So, to answer your question we will expand into all those areas. How we do it is another question, because it’s a huge area. It’s a huge undertaking because we’re already behind in terms of new media. And we also have another great museum here in town that does that kind of new media work. So we will have to find a niche for this type of work within the MIA collection, which we are in the process of doing for new media.

On a side note, I find it interesting that a lot of artists who are creating in film or experimental video are really looking at, or inspired by, photography as much as they are by film. As well as the other fine arts. So this makes the photography department an even better place for video and new media to be located.

One thing I’ve been really curious about thinking from a fine arts standpoint is, do you place a distinction between a photograph that was created in a film format versus one created in a digital format? Or do you feel a digital camera is just the next tool in the timeline of creating photographs?

For me it’s not about the tool, it’s about the image. I will sometimes ask, of course, if it’s a digital image because it might tell me more information about the image itself. But we don’t really make any of those distinctions. I think that there was a tradition within this department, as well as other departments, to make more of those distinctions. But if one were to do that you’d probably miss most of what happened in the last 30 years and particularly what’s happening now; if you really restricted yourself to certain machines or certain traditions.

So I’m more interested in the image than I am in technique. The whole digital question is a fascinating one, because one of the more interesting things I’ve heard said about digital is that digital is sometimes aspiring for film, and I think the digital photographers who are doing the most interesting things now are accepting the attributes of digital and using those in their production and not being caught in the in-between of analog verses digital worlds.

To me digital is digital. It has it’s own qualities and there is generally a noticeable visual difference. Your eyes know the difference. But the important thing is that I don’t place a judgment value on the differences between film and digital images. Again, in the end it all comes back to the image, what is actually in front of you.

It all comes back to the art then?

Art is part of it, but another part of it is the power of the image. The raw power, the historical power, and the importance of the image. Because I think the other part of that is that there are photographs that we could buy in the future or make part of the collection that weren’t made within an art context. Images that weren’t even made by an artist. And I think that you’ll see more and more of that in our collecting in the future. And in some cases we might collect images that were not made by a ‘photographer,’ they could be images created by an artist who is making a picture but photography is not their main medium.

You mentioned already how many pieces you have. How do you determine what ends up in the gallery space at any given time? Do you have a seasonal rotation?

There are two exhibitions a year. But we’re always trying to figure out ways we can showcase our collection because we’ve spent the museum’s resources to own our collection. When we get works from artists and put them in the collection it is a part of our obligation to show that work as much as possible. In terms of what goes up for public view during these exhibitions a lot of time it is based on a theme. But, there are some special images like the Migrant Mother our Dorothy Lang piece, which is one of our signature pieces that will always be in the rotation.

A lot of the works in our Masterpiece book are so well known to the public they are up for public view most of the year. When going through the collection I have to think about what pieces haven’t been on view in two years and figure out ways to get them out into the rotation that makes sense for whatever theme we are working with at the time. It can be a complex thing sometimes.

There was a time when Starry Night was off the wall and it was awful because people would travel from Ireland or come from China for their one visit to the MIA and they’d say, “where is Starry Night?!” They’d come just for that painting. So we have to think a little bit about that as well. We don’t have quite that level of masterpieces in our area, but we have few images that people like to see, so that is a kind of exception in terms of how I choose pieces that will be shown at any given time.

How do you determine new pieces that you’re going to collect? Or rather, how do you add pieces to the collection?

You make a plan. It starts with that.

Like a business plan?

It’s not quite a business plan. It’s more of a shopping plan. Kind of like going into your closet and seeing that you’ve got 5 pairs of black pants and 3 brown jackets and then thinking maybe you need a blue jacket. In terms of art the way that that plays out is like how we just bought this Martin Parr here (he points to a photo on the wall in his office). Martin Parr is an important British photographer, probably one of the leading British photographers, a leading Magnum photographer and a major figure in the 80’s and 90s. But we didn’t have a Martin Parr image here at the MIA. So, it’s like one of those things, we didn’t have a tux…. we needed one, so we went out and got that picture. As a curator you need to look at important figures, figures that you want to support, and you see what you already have in your collection. One buying case might be that we don’t have something that we should so it becomes a no brainer, we need to get a piece by that given artist. Or in another case you might think we’ve got a lot of pieces by Alex Soth, but the best piece he ever did was X, and we don’t have that piece. So maybe you try to figure out a way to get a given artists’ best or most famous piece. There are a lot of ways to think about adding to a collection….

So you might buy a piece to round out a certain aspect of the collection?

Yes, in some cases that’s the idea. We only have work by Jill Perez from the 60’s, but we don’t have any of her work from the 80’s or the 90’s, and we might want to do that. Or you might decide photographer Y or Z he or she was producing strong work in the 80’s, but their 90’s work isn’t very strong so we won’t add anything from that period of time in their career.

Any way you look at it it’s a massive undertaking. It’s always a work in progress because you’re looking at time periods, you’re looking at categories, and you’re looking at individual artists. And at the end of the day you’re also looking at what the collection looks like as a whole. You’re asking yourself, “What does the MIA collection represent?” And then you look at that whole collection in relationship to the other locally based museums and think of the MIA collection in relationship to these other bodies of work. This becomes a complex thing; when you’re thinking in terms of entire museum collections as they relate to each other.

For me, I don’t want to have a collection that looks like everyone else’s collection. Which tends to happen a lot in this arena. But, I guess it happens in all facets of life as well. People tend to buy or do the same things and we have to ask ourselves, “How are we going to distinguish our collection?” But that’s a big question, right? And it is also the fun part. It is like putting together your most ideal sports team. Who wouldn’t like to think about having all their favorite sports heros on the same team at the same time?! Right?!

Along those same lines is it your job as the curator of photography to set this theme in motion and determine the vision you have for the museum?

Yep, that’s exactly it…. to a point. When I came to the MIA it already had a certain identity and a part of my job is to understand the institution and its history and build off of that. I don’t feel it is my job to change the direction the museum was taking in the past, but to take control of where we are headed now. I’m here to refresh our vision.

If you worked at a different museum would you have a totally different mission?

Yes. It would be a different mission and I would almost certainly collect pieces by different artists or different pieces by the same artist. For example, if you give me five works by a given artist if I were working for the Whitney I would choose one, but since I’m now working for the MIA I would likely choose a different piece. The idea is that there may be a best piece by an artist, but then there is also the best for your institution and sometimes that could be the same piece. But, a lot of the time it wouldn’t be the same choice.

When buying new pieces are you actually purchasing them from auction houses like Christy’s or Sotheby’s?

We can do that once and a while.

Are you operating on the same market as anybody else? There’s not a museum discount or anything liked that is there?

Priced the same.

How much work are you purchasing from artists themselves, specifically? Does that happen? Or is it usually through dealers?

It does happen. It happens sometimes. I don’t know the percentage, but sometimes we purchase from artists, sometimes from auctions, and sometimes from dealers. Most of the time we purchase work from dealers because most of the artists that we end up selecting are represented by a dealer. Not all of them but most of them, generally.

And you do get donations to the collection, too?

We get donations, as well.

How does that work? Is that usually coming from private parties?

They do come from private parties, and then those donations are treated almost like purchases. They’re evaluated and sometimes we say no and sometimes we say yes. It’s not a pro forma that if they’re offered that they’re accepted. Because that’s also a part of our collection plan. When someone offers me something I decide whether it fits within our plan and then you go forward from there.

Would you ever say, “That’s a great piece but it doesn’t fit in our plan.” ?

Well, you know what it’s like — How many shirts have you gotten from your grandmother that sit in your closet for years and years, and you feel bad about it, but you still don’t ever wear them. Not to compare fine art to the shirts your grandmother gave you for Christmas, but you get the picture. We don’t want to take an image that doesn’t do anyone any good if we have it in our collection. The other major factor involved in the decision making process for museums is about time and money. We have to mange, maintain, and insure our whole collection. This is really our number one job as a museum — to preserve and protect the work.

How much communication do you have with curators at other museums? Is it fairly open? Or is it competitive? Or do you not communicate with each other?

We do communicate with one another. And just like in any other field it is competitive with some people and not as competitive with others. But generally it’s pretty innocuous. It’s not a super competitive job. We’re not on the front page of the newspaper with a headline like, “David Little got the next ‘big named X’ piece before the Museum of Modern Art.” That type of issues comes up for other areas within the museum, like paintings, there is only one… so whatever museum has it has the only copy. With photography there are usually five to seven prints, so we’ve got a shot at getting a specific piece of work if we want it. We are aware of what our peers or collecting, but again it’s not super competitive.

Do you have a favorite photographer? Or a favorite few photographers or a favorite piece?

You know, it’s funny, I don’t. I like lots of pieces, and I certainly have favorites within certain artists bodies of work or genres. I love Marcel Duchamp’s work. I’ve always been a great admirer of his. I tend to admire artists that I would say are sort of non-photographers in a way, they are sculptures, or have some other fine arts focus, but then also create photographs…. For example, I love Man Ray. He was an artist that didn’t stick to a defined path or artistic discipline.

Do you know of any or hear rumblings of really new voices in the fine arts photo world? Is there like, oh man this guy is being collected by 10 museums?

You know what, I wouldn’t tell you that if I did. That’s the one thing I wouldn’t tell you. If I wanted to tell someone a tip like that I might tell it to a collector who I know will buy a piece and then give it to us!

So that is a guarded thought?

Yeah, you don’t want to talk about it – you can’t spend a lot of time talking about who you’re collecting or who you’re thinking about anyway with all your other responsibilities as a curator. But, there are always young photographers. I wouldn’t say that there’s ever any one person that’s really, really standing out above everyone else. One of the ways you could find who I like or think is new talent is by coming to our New Pictures series. That’s what that series is all about. It was created to highlight young photographer, as well as mid-career artists, who I think are doing important work.

That is my way of letting people know who I think are artists to watch. I’m not claiming that they’re going to be the next superstar, but I’m more or less saying, let’s take a closer look at that person. And hopefully as the series moves forward it will expand to feature multiple photographers each round instead of featuring just one at a time like we are now. So you’ll get to see more of a trend of what’s happening as opposed to viewing a single persons work.

Do you choose the artists for the New Picture series?

Yes. I’ve chosen all the artist so far, but that probably will change at some point moving forward. In a few years we’ll have other curators selecting, maybe even artists selecting new photographers.

And did you start that program?

Yes, I did. We started it here last fall.

Have people been receptive to it?

It’s been great, actually really great. We’ve got another one coming up in February, so it will be interesting to see what kind of response we get as more people know about it.

Thoughts on the Future of Film

(This is a blog post I wrote originally for the Livebooks Resolve Blog on March 4th 2010. I had started a conversation with Miki Johnson about how so many negative blog posts were being written at that time about negative changes within the photo industry and the economic downturn that I wanted to write something more positive and something that was about the future. I put together an outline of about 16 thoughts I had at the time about where the industry was headed and we picked this topic as my first post. Miki left her gig as the Livebooks editor shortly after this went live and my series stopped after this first post. Some of the other thoughts I outlined at that time I still believe are valid and I will get around to writing about them here soon.)

(Clark Patrick is one of those photographers who I immediately fell into a 3-hour conversation with the first time we met. He’s young and smart and passionate and has very strong ideas about everything — especially photography, as you’ll see below. Tired of looking at the year behind us, Clark conceived a series of posts on where photography would go in the next year. First up: All about film. – Miki Johnson)

This Year in Photography: Film makes a comeback

We all know that over the last few years digital photography has grown by leaps and bounds. Digital image quality is getting better almost exponentially and computer editing tools are getting easier and faster for professionals and non-professionals alike.

What I would like to argue, however, is that analog, film-based forms of photography will make a huge comeback in the very near future — in fact, it’s already happening.

In 2007 Kodak conducted a survey of 9,000 professional photographers asking them if they still used film. Over 75% of those surveyed responded with a ‘yes’.

More recently, San Diego-based commercial shooter Robert Benson took a small survey of fellow professional shooters, asking who still uses film and for what purposes. The answers highlight why film is still an important choice for professionals.

In this interview Brian Finke says, “I almost exclusively shoot film … I get the, WOW, reaction when I pull the first Polaroid and everyone on set sees I’m shooting film. I am instantly seen as an art photographer…” I love Bryce Duffy’s explanation of how film differs from digital. He says, “It’s like listening to a vinyl record on a turntable through a Macintosh tube amp through good speakers versus listening to a high quality MP3 on your iPod through a pair of expensive speakers.”

Everybody’s Favorite Crappy Camera

To further understand why film will remain a serious force within the future of the photo industry, take a look at the skyrocketing popularity of the Holga film camera. In the past few years, websites likeLomography have made this camera a must-have for many hip young aspiring artists as well as established shooters reconnecting with their roots.

The Holga is also, arguably, the worst film camera ever made. It is made of cheap plastic, the lens is plastic, it only allows for minimal focusing control, its poor design and construction allows light to leak onto the unexposed film, and it almost requires modification to work. It’s like a little handheld photographic chaos creator. And in this way it epitomizes the best aspect of ‘analog’ imagemaking: You never really know what you’re going to get.

Plus, since the camera is so inexpensive, people also love modifying it and creating their own new cameras to further their own specific creative visions – on film. That whole idea is even at the core of the Lomographic Society’s 10 Golden Rules.

I feel the rise in digital photography has actually inspired many shooters to go back to using film, especially with simple cameras like the Holga. And there will be further digital backlash instigated by younger photographers who reject many aspects of the current digital world. These are the same types of people who will take down their on-line social network profiles, start handwriting letters, and block text messaging from their cell phones (or get ride of them altogether). These artists are the future analog creators. Growing up in a digital world, they have a fresh way to look at what the analog world means.

Give Me Polaroid or Give Me Death

More proof that film still matters can be found in the public’s response to Polaroid’s announcement that it would cancel its instant film lines in 2008. Save Polaroid was formed immediately and there was a massive response on Flickr from photographers all over the world. I personally received at least 10 e-mails from professional photographers the day it was announced.

The Save Polaroid movement was so strong, it inspired The Impossible Project, which lobbied to bring the instant film back. The Impossible Project has now taken over one of Polaroid’s former production plants and is set to release a black-and-white version of instant film within the next month. I’m excited to hear that 8×10 instant film might be back this year as well. You can watch a great video about all of it here. (Dave, I dig that hat and beard combo.)

In case you missed that timeline, Polaroid instant film production was canceled, production plants were disassembled, then they were brought back to life by a very dedicated fan base less than 18 months later. After that, let’s just say I’ve got a lot more faith in the instant film business than I do in the auto industry.

As a little aside, I’d like to remind you all the Fuji did not stop production of their instant film lines when Polaroid did and is still making various lines of instant film.

Art School Kids Grow Up Fast

As a professional you might be yelling at me through your computer something like, “Clark, that’s great that a bunch of hipster kids love playing with a Chinese toy camera and crying about Polaroid cutting off their fun instant pics, but come on, there is no serious market for this type of imagery in the commercial agency environment…” Although that may be true right now for agency work in general — I believe there is potential for its growth in the near future.

Here’s why: I personally know one under-30 commercial shooter who was commissioned for a fairly substantial agency assignment last year using a Holga and/or other types of Lomo cameras, specifically for that ‘look.’ And guess how old the art director was who wanted that ‘look.’ 24.

Film has a potentially big place in the commercial world because those fore-mentioned hipster kids are in art schools all over the country right now and in a few years they will be the art directors and creative directors hiring professional photographers. And they will want to see something else, something interesting to them, including something that isn’t digital. Obviously, digital isn’t going anywhere and will continue to grow and develop as the technology changes, but film is already on its way back.

A New Film Future

One major barrier I’m sure someone would bring up if I didn’t is the processing costs associated with film. In many ways, that was a huge part of film’s downfall in the first place as digital technologies became the cheaper option. My thought on this point is fairly simple. The use of film within the future of our industry will come back as a stylistic choice as opposed to a price-point choice. If a given shooter has a film look, he or she will be able to use film and the client will pay for it.

I also think photographers today can use much less film they did before digital options were available. It is possible to do a whole shoot using only a single sheet of film. Plus, there are always digital tools to back up your film shoots in case that one sheet doesn’t turn out. Part of the reason professional shooters used so much film before digital was because there was no back up. It had to be right on at least one piece of film.

The way I see it, film will come back strong before it even gets a chance to go out of style — just like ’80s fashion. Plus, I’m sure Terry Richardson will be partying with a junky 35mm camera somewhere for the rest of his life. As long as he is kickin’ it, we can all … keep on rockin’ in the film world! (Note: I wrote this last part before I knew how much of a sleaze-bag Terry is…)

What are your thoughts on the use of film in the professional photo world of the future?

Account Planner Interview 2: Brenna Whisney

(The second interview for this series featuring Account and Strategic Planners at advertising agencies worldwide was with Brenna Whisney a Planner, at Fallon based in Minneapolis.)

What is your job title? I’ve heard a number of different names for your role within the agency world – what are some of those names? What’s the most common job title for your role?

My job title is Planner. When I worked at Olson my job title was ‘Brand Anthropologist’ (which is borrowed from cultural anthropologist). Some other job titles include account planner, or insights manager/planner, but really all these job titles are confusing and don’t explain the job very deeply.

Now that we know your job title – what is your job or rather what do you do?

Planners are a bridge between the client and creatives. We figure out what the clients wants to say to their consumers and how to make their message relevant to them. And by trying to figure out a relevant way to communicate with the consumers we help our creative department get that message across.

Do you know much about the history of this role within the industry?

It started in Britain and developed from the 1970’s-90’s. The role was created out of a need for someone working outside of pure research and also outside of account services. Clients were starting to need more information on things that were not defined within the roles of other parts of the agency.

The job function continues to evolve. There is now a sort of classic school of thinking within planning. Russell Davies is an example of someone who is a part of that older school thinking. A lot of what planning is is following trends; trends in communication, trends in culture, on-line, in fashion, really we need to be tracking trends anywhere and everywhere — anything that might relate to the work our clients are doing. There are a ton of great websites I follow daily as a part of my job to be able to track trends. For example: PSFK, Trend Central, or Trend Watching to name a few.

(For a really good overview of account planning’s history check it out here.)

How do you work with or interact with other agency departments? -Specifically the creative department and art directors? Who or what departments do you interact with the most?

We work with the account team by co-authoring the client brief and putting in the mandatories. Such as, “Here is what we/(you) want to communicate…” Then the creatives take that information to build off of for the campaigns. We also check back in with the creatives to make sure their work meets the client message during the development process.

When doing research we might find that the word, ‘partnership’ is the right idea for what a given client is trying to communicate, but the word ‘partnership’ is the wrong term to convey that meaning in the ads because maybe in that clients’ industry it has a stigma associated with it or another reason along those lines. So we also spend time thinking about the meaning behind the messages we are trying to convey.

The account department is often thinking about things through the clients eyes while the creative department is thinking about things more from the consumers eyes. We sort of sit in the middle making sure the creatives don’t stray too far from what the client is trying to say and also making sure they have enough creative room to present what the client needs to say in a way that has impact.

The planner role is unique in the agency because it is one of the few roles where sometimes you need to tell the client that their message is wrong or a given approach will not work. Our clients have come to expect that as planners we’re the ones who essentially get to call them out on things that aren’t right. One of my former clients liked to call me the, ‘vegetables’ because our information was a part of what they needed to hear, but they didn’t necessarily like hearing it.

When working with clients our job is to get them out of their own heads an into their customers heads and we do this in between the account departments and the creative departments.

Are you involved in pitches?

Yes. When an RFP (request for proposal) comes in we do research and craft a strategy. This happens on a much faster timeline than the work we do for our current clients. We’ll put together a proposal strategy in one or two weeks instead of 4 months which is more typical for client projects. We also work very closely with the creative department on pitches.

How did you become a planner? What is a typical way to get a job as a planner?

First I had to learn this was a job that even existed since it is such a small part of the larger advertising industry. In college few people knew what this job was. Once I learned what it was I wanted to go straight into it, but there really isn’t a straight path into this role. Most people move into this role from somewhere else within the agency world or from a totally different angle like coming from academics. I was able to move straight into planning because I knew from the start it was what I wanted to do, but that is rare.

Are you ever contacted by photographers?

No.

Are you surprised or wonder why?

Yes. Sort of…. we use a lot of imagery in our work and working directly with higher level photographers could benefit what we do.

How do planners use images?

We use images for our presentations. So we do image sorts to find images we need for those presentations. Sometimes we will build an entire presentation around a single image because it represents so strongly what we are trying to convey. Images are really important for us in our ability to telling a story. We also create images when we do consumer profiles. We will often visit with consumers to learn about them and document these people and their lives with photos. Then often this imagery gets used as a reference for the creative departments and for the clients as well.

Account Planner Interview 1: Heather Saucier

(My first planner interview for this series featuring Account and Strategic Planners at advertising agencies worldwide was with Heather Saucier a Sociologist, at Periscope based in Minneapolis.)

What is your job title? I’ve heard a number of different names for your role within the agency world – what are some of those names? What’s the most common job title for your role?

My job title is ‘Sociologist’. My background and degree is in sociology. At many agencies, ‘Account Planner’ is the most common title for my role. And some agencies call planners, ‘Insight Specialists’, Strategic Planners’, or ‘Brand Anthropologists’.

Why are there so many different titles for your role within the agencies?

What we are doing now and what we study has changed over time so the title has changed as well. The role is more complex now than it has been in the past.

Now that we know your job title – what is your job? What do you do?

A way that I like to frame it is that I have to go up high and wide to then come back down to create strategy for my clients. This means that sometimes I’m out shopping, sometimes I’m reading the news, and sometimes I’m asking questions of specific groups of people. I take all this information and tell stories about people and their behaviors. A good way to think about it is that I’m gathering all kinds of information and acting as an information translator. I help brands understand people and their behaviors better.

How do you do that specifically?

At Periscope we use a proprietary tool that has 11 categories of cultural trends that we believe everyone thinks about or is a part of their lives now. The goal is to really get our client to think more about their consumers and less about their own products, services, or themselves. Most companies know and care about their own businesses so much they don’t realize their customers don’t care about their company as much as they do.

Do you know much about the history of this role within the industry?

Account planning started in Britain in the early 1990’s so it’s not a brand new role within the industry, but it’s also not that old either in relation to other jobs in our industry.

How do you work with or interact with other agency departments? Specifically, the creative department and art directors? Who or what departments do you interact with the most?

We interact with the whole agency, but our time is fairly equally split between the account and creative departments. We have different relationships with each department. Account people tend to be more frustrated with our relationship because we are often challenging our clients to think in a new way and their job is to essentially keep the client happy. When we try to get them to change the way they think about their business this can upset the status quo, which makes the account departments job more challenging. On the other hand the creative department generally really likes working with our department because we are opening new avenues for ideas and helping back up their ideas with our research. I personally work a lot with copywriters and art directors. I provide them with research and information, which helps give them more of a voice in the creation of ads.

How is the information that your department generates used?

We tell stories about people and groups of people. We do this most often by creating visual representations of our information and we also use our research to help develop new products or services for our clients. All of our research is presented in a very visual way.

How are you connected to the client – do you ever communicate with them directly? Are you involved in pitches?

Yes, we communicate with all of our clients directly. And yes, we are also involved in most of our agencies’ pitches. We’re there to offer a fresh perspective.

How many planners does an agency usually have? Are there planners that play different roles within their own agencies or do some planners specialize in certain areas?

It depends on the size of the agency. At Periscope we’ve got 10 planners, which is about right for the overall size of our agency, but some places might have only person doing each aspect of our job and there are entire companies that only do planning – essentially planner agencies.

And yes, planners do have specialties. These specialties are usually around specific demographical groups of people like the baby boomers, millennials, or Hispanics. It’s really important that if a planner has a specialty in a certain area that they know it very well because it’s important the information they present around a specific type of group is well researched and legitimate.

How do you become a planner? Or what is a typical way to get a job as a planner?

My way into the industry was from a non-traditional path. I didn’t go to school for advertising or marketing. But, advertising is in my family. And it seems most planners also have a non-traditional path that leads them to this role. At its core it’s about fresh thinking. We have a hunger and curiosity to speak a truth. We are here to see realities as they are – not what our clients or we want them to be.

Do you ever work with photographers?

Yes, but we have an in-house photo studio and they usually cover our photo needs. But, there is more and more of a need for better and more authentic imagery to help us tell our stories. An issue we face in the photographs we use to represent our research is how do you interview and photograph someone and not disturb their environment? OR rather, how can we photograph people in the most honest way? A specific photographer’s eye or style of shooting can become really important in that process. We often use a sort of paparazzi style of photography to present our work. It helps us see and present what people are wearing and doing in their element. Good photography can make a huge difference in our storytelling process. Iphone photos are often just not compelling enough. Besides our in-house photographers we all use resources like Flickr and stock photo sites. But, these resources often don’t have images that represent the kind of photo opportunities we need. It’s very hard to find photographs of people in real life situations that are also high quality images.

Have you ever been contacted by a freelance photographer?

Never. (Besides me…)

Do you think there is a reason a planner could hire a photographer?

Yes. We could possibly hire photographers to take photos on the research side. It’s becoming more and more important for us to have better assets in our presentation. A photographer would have a more stylized way of presenting what we are trying to convey. Photographers could also be used to document events especially those that we organize within the community.

If a photographer could be useful to communicate with for a given project from a planner’s perspective how do you think that process could or should work?

Well, we would first need to create a space within the industry and within our own workflow for a photographer to get hired. And then we would need to figure out what that meant for a given project. Would a photographer be needed for a few hours, a few days, or weeks?

It is possible for a photographer to find a way to specialize in areas where we need good, honest, and compelling imagery like capturing boomers, children, or people eating in a natural way – like their daily food ceremonies, etc.

At a certain point photography becomes an investment for us as planners. In advertising, just like the culture outside of our industry there are individuals who want to hold on to what was, and some people who want to run right away into what is the new thing, and then there are people that fall somewhere in the middle. Planners are often looking and thinking about the future, but have to work in the middle because so many people within the industry want to think about things including photography and how it can be used in an old way.

Any other thoughts – related to photography or imagery in relation to your role?

Because a huge amount of our time is spent on research and thinking about how people communicate and connect I’ve become a fan of the work of Kansas State University professor Michael Wesch who teaches digital ethnography and cultural anthropology. A few years ago he created a YouTube video called, “The Machine is Us/ing Us” which highlights how text means something different on-line than it did before the internet and in that video he also starts to show how photos and video are now interactive things, not just static things. He’s done other projects with his students where they explore YouTube in a new way as well. It’s fascinating stuff.

When you really dig into Flickr & Youtube it reveals the scariness of being in front of a camera. There is a lot going on now culturally because of the truth we are all in front of or interacting with cameras constantly. This has an impact on the way people interact with brands and in-turn brands need to interact with people.

Do or do not there is no try. ~Yoda

Listening Carefully: The Jedi Student

Over the last five years my life has been completely consumed both personally and professionally with photography. During that time the commercial photographic industry has changed so rapidly and dramatically that every professional photographer I know has struggled in some way with one of the major changes that has happened since my entry into this profession.

One of the most obvious and major changes was the transition from film to digital. Although, film may be an artistic choice now, it is most certainly not the standard for creating and delivering images to clients. But, in 2002, less than a decade ago – digital photography was barely an option for the professional market. This singular change is so great I could write books on the topic, but even this reality is only a small part of the much bigger puzzle. Which is the question all professional photographers should be asking themselves, “Where are we now?” And, “Where is this business going?” The key word being business.

Because photography is my career and I’m a research orientated type of person I’ve put a huge amount of effort into trying to understand what is happening within this business from all sides. In my effort to understand what is going on I have reached out to a lot of industry leaders. I have met with, interviewed, e-mailed, or had phone conversations with reps/agents, other commercial photographers with various focus areas, talked and worked with assistants, and digital techs, reached out to writers, bloggers, camera manufactures, and just about anyone else connected to the industry. As well as read just about every single photographic publication I could get my hands on. Even going as far as reading articles from before I owned my first camera to give me a foundation for understanding where we find ourselves now.

But perhaps my greatest teacher and guide has come from my own professional experience in working with clients, art buyers, art directors, creative directors, editors, curators, printers, etc. and working directly with small businesses, or bands, and especially the overall mass of individuals you end up dealing with on a day to day basis while working towards getting an image created.

Beyond these things I read a lot of blogs. I now follow close to 300 blogs related to photography. One of the things that attracts me to the blog-o-sphere is that bloggers put a lot of their own opinions into what they write about. In some ways this makes the information more helpful because it is coming from their personal experience on or about what is happening right now. Having so many people writing so freely lends itself to more honesty.

On the flip side blogs can be less helpful for a reader because many bloggers don’t put out information that is based on solid facts or their posts are often not clearly researched so their opinions come across as random rants that aren’t very well articulated or clearly thought out. In other words, as an avid blog reader I have to sort through a lot of crap to find information that is accurate, helpful, and/or interesting and worthwhile.

Nonetheless so many people are sharing their insights on what is going on in our industry that if you’re paying attention and looking really hard you can get a good idea of where the actual problems and positives are within the world of photography. You can even get good clues as to where things will be in the future.

Over the last two years I’ve spent a lot of time commenting on other people’s blog posts but done little formal writing myself. However, I’ve been planning to start my own blog around issues within the commercial and wider photography world, but needed the last couple years to learn, listen, and develop ideas I felt are worth writing about. I’ve been taking a lot of notes, writing outlines, and scribbling down random collections of thoughts during the same time I’ve been reading other people’s work and feel now is the time for me to open my ideas to a wider audience.

One thing that will become a common thread throughout my writing in this blog is how much I disagree with a lot of the things I have read or are even considered common conventions within this business. Saying something a thousands times over doesn’t mean it is accurate or helpful. I will write about things that go against the grain. I feel it is important for me to write about things I disagree with because there are fewer people willing to call out the norm than those willing to go along with status quo so as not to come across as the bad guy. I’m not afraid of being the bad guy if it means presenting a more honest picture of what is going on in our industry right now.

Another thing I will spend a lot of time writing about for this blog will be my thoughts on the future of photography — the future as it relates to business, art, culture, anything and everything that presents a clue as to where we’re collectively headed.

And finally, this blog is going to be a place for me to write out loud about the direction I’m taking my own career because I finally feel like I understand what sets me apart from other photographers and why I take the approach that I take to my work, my art, and my business.

Speaking Carefully: The Jedi Teacher

The idea behind ‘The Photo Jedi’ comes from a very common theme I read, or hear, or feel like is one of the most common misconceptions about photography in general — which is that photography is ultimately about the camera. Almost every single person I tell I’m a professional photographer to asks the same first question, “What camera do you use/have?”

A camera is a tool. It’s nothing more and nothing less than that and anyone with money can buy one. When you build a house you use tools and you use the right tools for the job, but you’re tools won’t help you much if you don’t have an idea how you’re going to build the house in the first place. Many people have a very hard time separating the tool from the process when it comes to photography.

‘The Photo Jedi’ is my metaphor for conveying this point. As we have all come to know via popular culture the Jedi’s power comes from within their own minds and the use of the ‘force’. And not from any sort of tool they may or may not have.

Although, the light-saber and the camera might be considered one in the same for ‘The Photo Jedi’s” among us.

Besides that it doesn’t hurt that Obama, Mr. T, Chuck Norris, ET, Ewoks, and some awesome squirrels are also Jedi warriors for me to hang out with.

Ready, set, about to starting blogging your face off….